Croesus

| Croesus | |

|---|---|

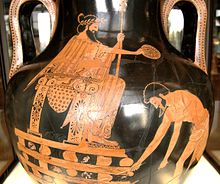

Depiction of Croesus, Attic red-figure amphora, painted c. 500–490 BC | |

| King of Lydia | |

| Reign | c. 585 – c. 546 BC |

| Predecessor | Alyattes of Lydia |

| Successor | Cyrus II of Persia |

| Born | 7th/6th century BCE Lydia Kingdom |

| Died | 6th century BCE Sardis, Turkey |

| Issue | 2, including Atys |

| Lydian | 𐤨𐤭𐤬𐤥𐤦𐤮𐤠𐤮 (Krowisas) |

| Father | Alyattes of Lydia |

Croesus (/ˈkriːsəs/ KREE-səs; Lydian: 𐤨𐤭𐤬𐤥𐤦𐤮𐤠𐤮 Krowisas;[1] Phrygian: Akriaewais;[2] Ancient Greek: Κροῖσος, romanized: Kroisos; Latin: Croesus; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC[3]) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.[4][3] According to Herodotus, he reigned 14 years. Croesus was renowned for his wealth; Herodotus and Pausanias noted that his gifts were preserved at Delphi.[5] The fall of Croesus had a profound effect on the Greeks, providing a fixed point in their calendar. "By the fifth century at least", J. A. S. Evans has remarked, "Croesus had become a figure of myth, who stood outside the conventional restraints of chronology."[6]

Name[edit]

The name of Croesus was not attested in contemporary inscriptions in the Lydian language. In 2019, D. Sasseville and K. Euler published a research of Lydian coins apparently minted during his rule, where the name of the ruler was rendered as Qλdãns.[7]

The name Croesus comes from the Latin transliteration of the Greek Κροισος Kroisos, which was thought to be the ancient Hellenic adaptation of the reconstructed Lydian name 𐤨𐤭𐤬𐤥𐤦𐤮𐤠𐤮 Krowisas.[1] Krowisas was also analyzed as a compound term consisting of the proper name 𐤨𐤠𐤭𐤬𐤮 Karoś, of a glide 𐤥 (-w-) and of the Lydian term 𐤦𐤮𐤠𐤮 iśaś, perhaps meaning "master, lord, noble".[1] According to J. M. Kearns, Croesus's real personal name would have been Karoś, while Krowisas would have been a honorific name meaning "The noble Karoś".[1]

Life and reign[edit]

Croesus was born in 620 BC to the king Alyattes of Lydia and one of his queens, a Carian noblewoman whose name is still unknown. Croesus had at least one full sister, Aryenis, as well as a step-brother named Pantaleon, born from a Ionian wife of Alyattes.[8][9]

Under his father's reign, Croesus had been a governor of Adramyttium, which Alyattes had rebuilt as a centre of operations for military actions against the Cimmerians, a nomadic people from the Pontic steppe who had invaded Western Asia, and attacked Lydia over the course of several invasions during which they killed Alyattes's great-grandfather Gyges, and possibly his grandfather Ardys and his father Sadyattes. As governor of Adramyttium, Croesus had to provide his father with Ionian Greek mercenaries for a military campaign in Caria.[10][11][8]

During Croesus's tenure as governor of Adramyttium itself, a rivalry had developed between him and his step-brother Pantaleon, who might have been intended by Alyattes to be his successor. Following Alyattes's death in 585 BC, this rivalry became an open succession struggle out of which Croesus emerged victorious.[8]

Conquests[edit]

Once Croesus's position as king was secure, he immediately launched a military campaign against the Ionian city of Ephesus. The ruling dynasty of Ephesus had engaged in friendly relations with Lydia consolidated by diplomatic marriages from the reign of Gyges until that of Alyattes: the Ephesian tyrant Pindar, who had previously supported Pantaleon in the Lydian succession struggle, was the son of a daughter of Alyattes, and was thus a nephew of Croesus. After Pindar rejected an envoy by Croesus demanding Ephesus to submit to Lydia, the Lydian king started to pressure the city and demanded that Pindar leave it and go into exile. After Pindar accepted these terms, Croesus annexed Ephesus into the Lydian Empire. Once Ephesus was under Lydian rule, Croesus provided patronage for the reconstruction of the Temple of Artemis, to which he offered a large number of marble columns as dedication to the goddess.[8]

Meanwhile the Ionian city of Miletus had been willingly sending tribute to Mena in exchange of being spared from Lydian attacks because the overthrow of the city's last tyrants, Thoas and Damasenor, and the replacement of the tyranny by a system of magistrates had annulated the relations of friendship initiated by Alyattes and the former Milesian tyrant Thrasybulus.[8]

Croesus continued his attacks against the other Greek cities of the western coast of Asia Minor until he had subjugated all of mainland Ionia, Aeolis, and Doris, but he abandoned his plans of annexing the Greek city-states on the islands and he instead concluded treaties of friendship with them, which might have helped him participate in the lucrative trade the Aegean Greeks carried out with Egypt at Naucratis.[8]

Other domains of the Lydian Empire under Croesus[edit]

The Lydians had already conquered Phrygia under the rule of Alyattes, who took advantage of the weakening of the various polities all across Anatolia by the Cimmerian raids and used the lack of a centralised Phrygian state and the traditionally friendly relations between the Lydian and Phrygian elites to extend Lydian rule eastwards to Phrygia. Lydian presence in Phrygia is archaeologically attested by the existence of a Lydian citadel in the Phrygian capital of Gordion, as well as Lydian architectural remains in northwest Phrygia, such as in Dascylium, and in the Phrygian Highlands at Midas City. Lydian troops might have been stationed in the aforementioned locations as well as in Hacıtuğrul, Afyonkarahisar, and Konya, which would have provided to the Lydian kingdom access to the produce and roads of Phrygia. The presence of a Lydian ivory plaque at Kerkenes Daǧ suggests that Alyattes's control of Phrygia might have extended to the east of the Halys River to include the city of Pteria, with the possibility that he may have rebuilt this city and placed a Phrygian ruler there: Pteria's strategic location would have been useful in protecting the Lydian Empire from attacks from the east, and its proximity to the Royal Road would have made of the city an important centre from which caravans could be protected. [2][12] Phrygia under Lydian rule would continue to be administered by its local elites, such as the ruler of Midas City who held Phrygian royal titles such as lawagetai (king) and wanaktei (commander of the armies), but were under the authority of the Lydian kings of Sardis and had a Lydian diplomatic presence at their court, following the framework of the traditional vassalage treaties used since the period of the Hittite and Assyrian empires, and according to which the Lydian king imposed on the vassal rulers a "treaty of vassalage" which allowed the local Phrygian rulers to remain in power, in exchange of which the Phrygian vassals had the duty to provide military support and sometimes offer rich tribute to the Lydian kingdom.[2]

This situation continued under the rule of Croesus, with one inscription attesting of the presence of Croesus's son Atys at the court of one local ruler of Midas City himself named Midas. At Midas City, Atys held the position of priest of the sacred fire of the mother goddess Aryastin, and through him Croesus provided patronage to the building of the religious monument in the city now known as the Midas Monument.[2]

The presence of Atys at the court of this Midas might have inspired the legend recounted by Herodotus, according to which Croesus had a dream in which Atys was killed by an iron spear, after which he prevented his son from leading military activities, but Atys nevertheless found death while hunting a wild boar which was ravaging Lydia, during which he was accidentally hit by the spear thrown by the Phrygian prince Adrastus, who had previously exiled himself to Lydia after accidentally killing his own brother.[13]

Croesus also brought Caria, whose various city-states had since Gyges been allied to the Mermnad dynasty, and from where Croesus's own mother originated, under the direct control of the Lydian Empire.[8]

Thus, according to Herodotus, Croesus ruled over all the peoples to the west of the Halys River - the Lydians, Phrygians, Mysians, Mariandyni, Chalybes, Paphlagonians, Thyni and Bithyni Thracians, Carians, Ionians, Dorians, Aeolians, and Pamphylians. However information only about the relations between the Lydians and the Phrygians is attested in both literary and archaeological sources, and there is no available data concerning relations between the other mentioned peoples and the Lydian kings; moreover, given this was the situation detailed by Herodotus under the reign of Croesus, it is very likely that a number of these populations had already been conquered under Alyattes. The only populations Herodotus claimed were independent of the Lydian Empire were the Lycians, who lived in a mountainous country which would not have been accessible to the Lydian armies, and the Cilicians, who had already been conquered by Neo-Babylonian Empire. Modern estimates nevertheless suggest that it is not impossible that the Lydians might have subjected Lycia, given that the Lycian coast would have been important for the Lydians because it was close to a trade route connecting the Aegean region, the Levant, and Cyprus.[2] Modern studies also consider doubtful the Graeco-Roman historians' traditional account of the Halys River as having been set as the border between the Lydian and the Median kingdom, which appears to have been a retroactive narrative construction based on symbolic role assigned by Greeks to the Halys as the separation between Lower Asia and Upper Asia as well as on the Halys being a later provincial border within the Achaemenid Empire. The eastern border of the kingdom of Croesus would thus have instead been further to the east of the Halys, at an undetermined point in eastern Anatolia.[14][15][2][16][17]

International relations[edit]

Croesus continued the friendly relations with the Medes concluded by his father Alyattes and the Median king Cyaxares after five years of war in 585 BC, shortly before both their respective deaths that same year. As part of the peace treaty ending the war between Media and Lydia, Croesus's sister Aryenis had married Cyaxares's son and successor Astyages, who thus became Croesus's brother-in-law, while a daughter of Cyaxares might have been married to Croesus. Croesus continued these good relations with the Medes after he succeeded Alyattes and Astyages succeeded Cyaxares.[2]

Under Croesus's rule, Lydia continued its good relations started by Gyges with the Saite Egyptian kingdom, then ruled by the pharaoh Amasis II. Both Croesus and Amasis had common interests in fostering trade relations at Naucratis with the Greeks, including with the Milesians who were under Lydian authority. These trade relations also functioned as an access point for Greek mercenaries serving the Saite pharaohs.[2]

Croesus also established trade and diplomatic relations with the Neo-Babylonian Empire of Nabonidus, which ensured the transition of Lydian products towards Babylonian markets.[2]

Votive offerings to Delphi[edit]

Croesus also continued the good relations between Lydia and the sanctuary of the god Apollo in Delphi on continental Greece first established by his great-great-grandfather Gyges and maintained by his father Alyattes, and just like his ancestors, Croesus offered the sanctuary rich presents in dedication, including a lion made of gold and weighing ten talents. In exchange for the offerings of Croesus to the sanctuary of Apollo, the Lydians obtained precedence in consulting its oracle, were exempt from taxes, were allowed to sit at the first rank, and were granted the permission to become Delphian priests. These exchanges of gifts for privileges in turn meant that strong relations of hospitality existed between Lydia and Delphi due to which the Delphians had the duty to welcome, protect, and ensure the well-being of Lydian ambassadors.[6][8]

Croesus further increased his contacts with the Greeks on the European continent by establishing relations with the city-state of Sparta, to whom he provided the gold they needed to gild a statue of the god Apollo after the oracle of Delphi told them they would obtain this gold from Croesus.[8]

Coinage[edit]

Croesus is credited with issuing the first true gold coins with a standardised purity for general circulation, the Croeseid (following on from his father Alyattes who invented minting with electrum coins). Indeed, the invention of coinage had passed into Greek society through Hermodike II.[18][19] Hermodike II, the daughter of an Agamemnon of Cyme, claimed descent from the original Agamemnon who conquered Troy. She was likely one of Alyettes’ wives, so may have been Croesus’ mother, because the bull imagery on the croeseid symbolises the Hellenic Zeus—see Europa (consort of Zeus).[20] Zeus, through Hercules, was the divine forefather of his family line.

While the pyre was burning, it is said that a cloud passed under Hercules and with a peal of thunder wafted him up to heaven. Thereafter, he obtained immortality... by Omphale he had Agelaus, from whom the family of Croesus was descended...[21]

Moreover, the first coins were quite crude and made of electrum, a naturally occurring pale yellow alloy of gold and silver. The composition of these first coins was similar to alluvial deposits found in the silt of the Pactolus river (made famous by Midas), which ran through the Lydian capital, Sardis. Later coins, including some in the British Museum, were made from gold purified by heating with common salt to remove the silver.[22]

In Greek and Persian cultures the name of Croesus became a synonym for a wealthy man. He inherited great wealth from his father Alyattes, who had become associated with the Midas myth because Lydian precious metals came from the river Pactolus, in which King Midas supposedly washed away his ability to turn all he touched into gold.[23] In reality, Alyattes' tax revenues may have been the real 'Midas touch' financing his and Croesus' conquests. Croesus' wealth remained proverbial beyond classical antiquity: in English, expressions such as "rich as Croesus" or "richer than Croesus" are used to indicate great wealth to this day.[24] The earliest known such usage in English was John Gower's in Confessio amantis (1390):

|

Original text:

|

Modern spelling:

|

Interview with Solon[edit]

According to Herodotus, Croesus encountered the Greek sage Solon and showed him his enormous wealth.[26] Croesus, secure in his own wealth and happiness, asked Solon who the happiest man in the world was, and was disappointed by Solon's response that three had been happier than Croesus: Tellus, who died fighting for his country, and the brothers Kleobis and Biton who died peacefully in their sleep after their mother prayed for their perfect happiness because they had demonstrated filial piety by drawing her to a festival in an oxcart themselves.

Solon goes on to explain that Croesus cannot be the happiest man because the fickleness of fortune means that the happiness of a man's life cannot be judged until after his death. Sure enough, Croesus' hubristic happiness was reversed by the tragic deaths of his accidentally killed son and, according to Ctesias, his wife's suicide at the fall of Sardis, not to mention his defeat at the hands of the Persians.

The interview is in the nature of a philosophical disquisition on the subject "Which man is happy?" It is legendary rather than historical. Thus, the "happiness" of Croesus is presented as a moralistic exemplum of the fickleness of Tyche, a theme that gathered strength from the fourth century, revealing its late date. The story was later retold and elaborated by Ausonius in The Masque of the Seven Sages,[27] in the Suda (entry "Μᾶλλον ὁ Φρύξ," which adds Aesop and the Seven Sages of Greece),[28][29] and by Tolstoy in his short story "Croesus and Fate".

War against Persia and defeat[edit]

In 550 BC, Croesus's brother-in-law, the Median king Astyages, was overthrown by his own grandson, the Persian king Cyrus the Great.[2] In a likely legendary event recounted by Herodotus, Croesus responded by consulting the oracle of Delphi, who told him that he would "destroy a great empire" should he attack Cyrus. This answer of the Delphian oracle remains one of the famous oracular statements from Delphi.[2] Likely legendary were also the responses of the oracles of Delphi and Amphiaraus telling Croesus to ally with the strongest of all Greeks, whom Croesus found out to be the state to which he had previously offered the gold which they had used for the gilding of a statue of the god Apollo, Sparta, shortly after its victory over its fellow Greek city-state of Argos in 547 BC. The claim of Herodotus that Croesus, Amasis, and Nabonidus formed a defensive alliance against Cyrus of Persia appears to have been a retroactive exaggeration of the existing diplomatic and trade relations between Lydia, Egypt, and Babylon.[2]

Croesus first attacked Pteria, the capital of a Phrygian state vassal to the Lydians which might have attempted to rebel against Lydian suzerainty and instead declare its allegiance to the new Persian Empire of Cyrus. Cyrus retaliated by intervening in Cappadocia and attacking the Lydians at Pteria in a battle in which Croesus was defeated. After this first battle, Croesus burnt down Pteria to prevent Cyrus from using its strategic location and returned to Sardis. However, Cyrus followed Croesus and defeated the Lydian army again at Thymbra before besieging and capturing the Lydian capital of Sardis, thus bringing an end to the rule of the Mermnad dynasty and to the Lydian Empire. Lydia would never regain its independence and would remain a part of various successive empires.[2]

Although the dates for the battles of Pteria and Thymbra and of end of the Lydian empire have been traditionally fixed to 547 BC,[6] more recent estimates suggest that Herodotus's account being unreliable chronologically concerning the fall of Lydia means that there are currently no ways of dating the fall of Sardis; theoretically, it may even have taken place after the fall of Babylon in 539 BC.[6][30]

Later life and death[edit]

Croesus's fate after the Persian conquest of Lydia is uncertain: Herodotus, the poet Bacchylides and Nicolaus of Damascus claimed that Croesus either tried to commit suicide on a pyre or was condemned by the Persians to be burnt at the stake until a thunderstorm's rain water extinguished the fire after either his or his son's prayers to the god Apollo (or after Cyrus heard Croesus calling the name of Solon). In most versions of the story, Cyrus kept Croesus as his advisor, although Bacchylides claimed that the god Zeus carried Croesus away to Hyperborea. Xenophon similarly claimed that Cyrus kept Croesus as his advisor while Ctesias claimed that Cyrus appointed Croesus as the governor of the city of Barene in Media.[2][6]

A passage from the Nabonidus Chronicle was long held to have referred to a military campaign of Cyrus against a country whose name has been largely erased except for the first cuneiform character which had been interpreted as Lu, extrapolated to be the first syllable of an Akkadian name for Lydia. This passage in the Nabonidus Chronicle would thus have referred to a campaign by Cyrus against Lydia around 547 BC during which "marched against the country, killed its king, took his possessions, and put there a garrison of his own". However, the verb used in the Nabonidus Chronicle could be used both in the sense "to kill" and "to destroy as a military power", making any precise deduction of the fate of Croesus from it impossible.[6][31] More recent studies have moreover concluded that the non-erased character was Ú/U₂, making untenable the interpretation of the text as talking of a campaign against Lydia, and instead suggesting that the campaign was against Urartu.[30][32][33]

The scholar Max Mallowan argued that there is no evidence that Cyrus the Great killed Croesus, in particular rejected the account of burning on a pyre, and interpreted Bacchylides' narration as Croesus attempting suicide and then being saved by Cyrus.[34]

The historian Kevin Leloux instead maintained the reading of the Nabonidus Chronicle as referring to a campaign of Cyrus against Lydia to argue that Croesus was indeed executed by Cyrus. According to him, the story of Croesus and the pyre would have been imagined by the Greeks based on the fires started during the Persian capture of Sardis throughout the lower city, where the buildings were made largely of wood.[2]

In 2003, Stephanie West argued that the historical Croesus did in fact die on the pyre, and that the stories of him as a wise advisor to the courts of Cyrus and Cambyses are purely legendary, showing similarities to the sayings of Ahiqar.[35] A similar conclusion is drawn in a recent article that makes a case for the proposal that the Lydian word Qλdãnś, both meaning 'king' and the name of a god, and pronounced /kʷɾʲ'ðãns/ with four consecutive Lydian sounds unfamiliar to ancient Greeks, could correspond to Greek Κροισος, or Croesus. If the identification is correct it might have the interesting historical consequence that king Croesus chose suicide at the stake and was subsequently deified.[7]

Legacy[edit]

After defeating Croesus, Cyrus adopted the use of gold coinage as the main currency of his kingdom. The use of croesid coins under the Persian Empire would continue under Cyrus, and would end only after Darius the Great replaced them by the Persian daric. These late croesid coins bearing "bull and lion" images used under Cyrus differed from previous Mermnad croesids in that they were lighter and their weight was closer to those of the early golden darics and silver sigloi.[34]

In popular culture[edit]

According to the Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi (c. 410–490s AD), who wrote a monumental History of Armenia, the Armenian king Artaxias I accomplished many military deeds, which include the capture of Croesus and the conquest of the Lydian kingdom (2.12–13) [36] References to Croesus' legendary power and wealth, often as a symbol of human vanity, are numerous in literature.

The following, by Isaac Watts, is from the poem "False Greatness":

Another literary example is "Croesus and Fate", a short story by Leo Tolstoy that is a retelling of the account of Croesus as told by Herodotus and Plutarch.

Crœsus, King of Lydia, is a tragedy in five parts by Alfred Bate Richards, first published in 1845.

To be "riche comme Crésus" is a popular French saying to describe the wealthiest of the wealthy, and gave its name to a TF1 game show Crésus, where the king is reimagined as a CGI skeleton, who has returned from the dead to give some of his money away to lucky contestants.

On The Simpsons, the wealthy Montgomery Burns lives at the corner of Croesus and Mammon Streets.

In The Sopranos season 4 episode 6, Ralph Cifaretto tells Artie Bucco “With what you take out of that bar, you must be sitting on money like King Croesus.”

In Squidbillies season 6 episode 8, Dan Halen remarks that he paid Early Cuyler, who he said "left with cash in hand, rich as Croesus".

In East of Eden Chapter 34, John Steinbeck refers to Croesus to explain about living a righteous life. With time, wealth will vanish as did with Croesus. So, the question one should ask to determine whether one lived a good life is “Was he loved or was he hated? Is his death felt as a loss or does a kind of joy come of it?”

See also[edit]

- Croesus (opera)

- Karun Treasure ("Croesus treasure")

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Kearns, J.M. (1997). "A Lydian Etymology for the Name of Croesus". In Disterheft, Dorothy; Huld, Martin E.; Greppin, John A.C.; Polomé, Edgar C. (eds.). Studies in Honor of Jaan Puhvel-Part One: Ancient Languages and Philology. Washington D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man. pp. 23–28. ISBN 978-0-941-69454-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Leloux, Kevin (2018). La Lydie d'Alyatte et Crésus: Un royaume à la croisée des cités grecques et des monarchies orientales. Recherches sur son organisation interne et sa politique extérieure (PDF) (PhD). Vol. 2. University of Liège. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ a b Dale, Alexander (2015). "WALWET and KUKALIM: Lydian coin legends, dynastic succession, and the chronology of Mermnad kings". Kadmos. 54: 151–166. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2015-0008. S2CID 165043567. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Wallace, Robert W. (2016). "Redating Croesus: Herodotean Chronologies, and the Dates of the Earliest Coinages". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 136: 168–181. doi:10.1017/S0075426916000124. JSTOR 44157500. S2CID 164546627. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Among them a lion of gold, which had tumbled from its perch upon a stack of ingots when the temple at Delphi burned but was preserved and displayed in the Treasury of the Corinthians, where Pausanias saw it (Pausanias 10.5.13). The temple burned in the archonship of Erxicleides, 548–47 BC.

- ^ a b c d e f Evans, J. A. S. (1978). "What Happened to Croesus?". The Classical Journal. 74 (1): 34–40. JSTOR 3296933. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b Sasseville, David; Euler, Katrin (2019). "Die Identität des lydischen Qλdãns und seine kulturgeschichtlichen Folgen" [The identity of the Lydian Qλdan and its cultural-historical consequences]. Kadmos (in German). 58 (1/2): 125–156. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2019-0007. S2CID 220368367. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Leloux, Kevin (2018). La Lydie d'Alyatte et Crésus: Un royaume à la croisée des cités grecques et des monarchies orientales. Recherches sur son organisation interne et sa politique extérieure (PDF) (PhD). Vol. 1. University of Liège. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Accepting Dale's dating of Croesus's reign starting in 585 BC and Leloux's assumption of Croesus being 35 years old at the beginning of his reign provides a birth date of 620 BC

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 94–55.

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony J. (1978). "The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 98 (4): 400–409. doi:10.2307/599752. JSTOR 599752. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Mellink 1991, p. 643–655.

- ^ Strassler, Robert B. (2009). The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-1400031146.

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 125–126.

- ^ Leloux, Kevin (December 2016). "The Battle of the Eclipse". Polemos: Journal of Interdisciplinary Research on War and Peace. 19 (2). Polemos. hdl:2268/207259. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- ^ Rollinger, Robert (2003). "The Western Expansion of the Median 'Empire': A Re-Examination". In Lanfranchi, Giovanni B.; Roaf, Michael; Rollinger, Robert (eds.). Continuity of Empire (?) Assyria, Media, Persia. Padua: S.a.r.g.o.n. Editrice e Libreria. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-9-990-93968-2.

- ^ Lendering, Jona (2003). "Alyattes of Lydia". Livius. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Herodotus, I, p. 80

- ^ An Encyclopedia of World History, (Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, 1952), chap. II. "Ancient History", p. 37

- ^ Grimal, Pierre (1991). The Penguin dictionary of classical mythology. Kershaw, Stephen. (Abridged) ed. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140512357. OCLC 25246340.

- ^ Perseus 1:2.7– According to Hdt. 1.7 the dynasty which preceded that of Croesus on the throne of Sardes traced their descent from Alcaeus, the son of Herakles by a slave girl. It is a curious coincidence that Croesus, like his predecessor or ancestor Herakles, is said to have attempted to burn himself on a pyre when the Persians captured Sardes. See Bacch. 3.24–62, ed. Jebb. The tradition is supported by the representation of the scene on a red-figured vase, which may have been painted about forty years after the capture of Sardis and the death or captivity of Croesus. See Baumeister, Denkmäler des klassischen Altertums, ii.796, fig. 860. Compare Adonis, Attis, Osiris, 3rd ed. i.174ff. The Herakles whom Greek tradition associated with Omphale was probably an Oriental deity identical with the Sandan of Tarsus. See Adonis, Attis, Osiris, i.124ff.

- ^ "A History of the World-Episode 25 – Gold coin of Croesus". BBC British Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-02-27.

- ^ "BBC - A History of the World - Object: Gold coin of Croesus". BBC History.

- ^ "Longtermism: How good intentions and the rich created a dangerous creed". TheGuardian.com. 4 December 2022.

- ^ Confessio amantis, v. 4730. "Croesus". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Herodotus, The Histories, Book 1, chapter 29, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved Feb 19, 2023.

- ^ Ausonius, Decimus Magnus; Evelyn-White, Hugh G. (Hugh Gerard) (Feb 21, 1919). "Ausonius, with an English translation". London W. Heinemann. Retrieved Feb 19, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gazzano, Francesca; Castelnuovo, Luisa Moscati. Μᾶλλον ὁ Φρύξ. Creso e la sapienza greca – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Castelnuovo, Luisa Moscati (June 2016). Solone e Creso : variazioni letterarie, filosofiche e inconografiche su un tema erodoteo : atti della giornata di studi - Macerata 10 marzo 2015 (Primaizione ed.). Macerata. ISBN 978-88-6056-460-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Rollinger, Robert (2008). "The Median 'Empire', the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great's Campaign in 547 BC". Ancient West & East. 7: 51–66. doi:10.2143/AWE.7.0.2033252. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Cornelius, F. (1957). "Kroisos". Gymnasium. 64: 364–366.

- ^ Cargill, J. (1977). "The Nabonidus Chronicle and the fall of Lydia. Consensus with feet of clay". American Journal of Ancient History. 2: 97–116.

- ^ Oelsner, Joachim (1999–2000). "Reviewed Work: Herodots babylonischer Logos. (= Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, Sonderheft 84) by Robert Rollinger". Archiv für Orientforschung/Institut für Orientalistik. 46/47: 373–380. JSTOR 41668490. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b Mallowan, Max (1968). Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. pp. 392–419. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- ^ Stephanie West, "Croesus' Second Reprieve and Other Tales of the Persian Court", Classical Quarterly (n.s.) 53(2003): 416–437, esp. pp. 419–424.

- ^ [1] F. Gazzano, Croesus' Story in the History of Armenia of Movsēs Xorenac'i, in F. Gazzano, L. Pagani, G. Traina (eds.), Greek Texts and Armenian Traditions: An Interdisciplinary Approach (TiC Suppl, Vol. 39), Berlin-Boston 2016, 83–113.

- ^ Watts, Isaac (1762). Horae lyricae: poems, chiefly of the lyric kind ... /. New York : Printed and sold by Hugh Gaine.

- ^ "Horae Lyricae (Isaac Watts) – ChoralWiki". www2.cpdl.org. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

Works cited[edit]

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1985). "Media". In Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 36-148. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Mellink, M. (1991). "The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 619–665. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to Croesus at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Croesus at Wikiquote Media related to Croesus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Croesus at Wikimedia Commons- Crésus. Le plus riche des rois de Lydie, Perrin, Paris, 2023 by Kevin Leloux

- "L'alliance lydo-spartiate", in Ktèma, 39, 2014, pp. 271–288 by Kevin Leloux

- "Les alliances lydo-égyptienne et lydo-babylonienne", in Gephyra, 22, 2021, pp. 181–207 by Kevin Leloux

- Herodotus' account of Croesus; 1.6–94 (from the Perseus Project, containing links to both English and Greek versions). Croesus was the son of Alyattes and continued the conquest of Ionian cities of Asia Minor that his father had begun.

- An in-depth account of Croesus' life, by Carlos Parada

- Livius, Croesus Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine by Jona Lendering

- Croesus on Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Gold Coin of Croesus a BBC podcast from the series: "A History of the World in 100 Objects"

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.